When Hurricane Helene hit North Carolina in September 2024, the real crisis wasn’t just the flooded roads or the power outages. It was the empty shelves in hospital pharmacies. One plant in North Cove, owned by Baxter International, made 60% of the country’s IV fluids. When it went offline, hospitals across the U.S. had to stop elective surgeries, delay cancer treatments, and ration saline bags. Patients waited. Doctors scrambled. And the worst part? This wasn’t a one-off.

Why Hurricanes Are the Biggest Threat to Your Medicine

Hurricanes aren’t just big storms-they’re supply chain killers. Between 2017 and 2024, they caused nearly half of all climate-related drug shortages in the U.S. That’s more than wildfires, floods, and heatwaves combined. The reason? Concentration. The pharmaceutical industry doesn’t spread its production across the country. It piles it into a few key spots. Puerto Rico used to make 10% of all FDA-approved drugs and 40% of sterile injections. After Hurricane Maria in 2017, the island’s power grid collapsed. It took 11 months to fully restore electricity. Insulin, saline, antibiotics-those drugs vanished for over a year. Hospitals rationed. Patients got less. Some got nothing. Today, the same problem exists in Western North Carolina. Baxter’s North Cove plant still makes 1.5 million IV bags a day. Spruce Pine, just 90 miles away, supplies 90% of the high-purity quartz used in medical devices. One storm can knock out multiple critical links at once.One Factory, One Drug, No Backup

Most people assume there are multiple makers for every medicine. There aren’t. For 78% of sterile injectables in the U.S., there’s only one or two factories that make them. That’s not efficiency. It’s a single point of failure. Take the 2023 tornado that hit Pfizer’s Rocky Mount plant. It didn’t destroy the whole facility, but it knocked out a single production line. That line made 27 different medicines. Within days, those drugs started disappearing from pharmacies. The FDA predicted shortages would last until mid-2024. No other company could step in fast enough. Why? Because building a new drug factory isn’t like opening a coffee shop. It takes 6 to 12 months just to get the permits, and 2 to 3 years to install the specialized equipment needed for sterile production. You can’t just hire more workers and turn on the machines. The machines themselves are custom-built, expensive, and take forever to ship.Climate Change Is Making This Worse

This isn’t just about one bad hurricane season. It’s about the long-term trend. According to NOAA, the number of Category 4 and 5 hurricanes is expected to rise 25-30% by 2030. And here’s the scary part: 65.7% of all U.S. pharmaceutical manufacturing facilities are in counties that have had at least one federally declared weather disaster since 2018. The FDA now officially lists natural disasters as a top cause of drug shortages. And it’s not just hurricanes. Floods in Michigan in 2022 hit Abbott’s infant formula plant during an already critical shortage-extending the crisis by eight weeks. Wildfires in California have damaged packaging facilities. Even extreme heat can shut down sensitive production lines. The system wasn’t built for this. It was built for efficiency, not resilience. Just-in-time inventory means companies keep minimal stock on hand. Why? Because storing drugs costs money. But when disaster hits, there’s nothing to fall back on.

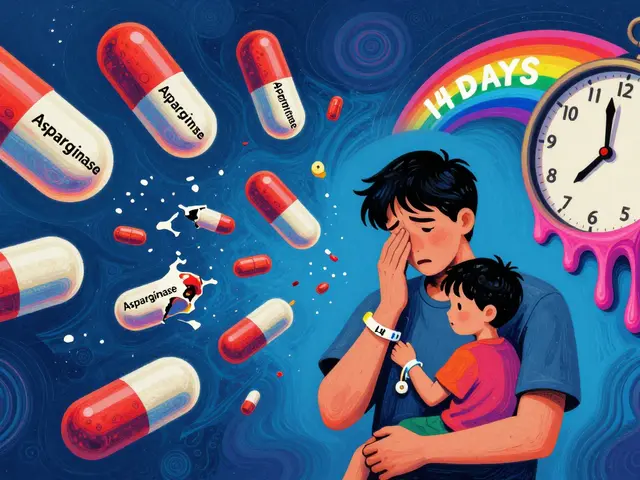

What Happens When the Medicine Runs Out

It’s not abstract. It’s personal. Cancer patients need sterile injectables for chemotherapy. Diabetics need insulin. Newborns need IV fluids to stay hydrated. When these drugs disappear, doctors make impossible choices. Do we give the last bag to the patient in the ER, or the one in the ICU? Do we delay a surgery that could save a life, or risk infection because we’re using a less effective substitute? The American Cancer Society found that cancer drugs-especially older, generic ones-are hit hardest. They’re cheap to make, so companies don’t invest in multiple factories. When a storm knocks out the only plant, there’s no backup. No competition. No price drop. Just silence. Hospitals are forced into crisis mode. Pharmacists spend 12-24 hours per product just trying to extend expiration dates. Nurses reuse IV tubing. Doctors switch to oral versions when they’re less effective. All of this adds stress, risk, and delays.Who’s Trying to Fix This?

Some people are trying. The FDA launched a new Critical Drug Resilience Program in January 2025. It fast-tracks approvals for manufacturers who spread production across three different climate-resilient regions. That’s a start. The Strategic National Stockpile now keeps emergency supplies of key injectables in hurricane-prone states. During Helene, that pilot program cut shortage duration by 40% compared to Maria. Hospitals with over 500 beds are 3.2 times more likely to map their supply chains than smaller clinics. That’s a problem. Rural hospitals and community health centers don’t have the staff or money to do this. When disaster strikes, they’re the last to know-and the first to suffer. The pharmaceutical industry is waking up. Sixty-eight percent of top drug makers now assess climate risks-up from 22% in 2020. But only 31% have actually done anything about it. Most are still waiting for regulations to force their hand.

What’s Coming Next

The FDA is proposing a new rule in 2025: manufacturers of critical drugs must keep 90-day emergency inventories and submit climate risk plans. That could cost them 4-7% more to produce, but it could prevent 60% of future shortages. Experts agree: we need more than just stockpiles. We need geographic diversity. We need redundancy. We need to stop treating medicine like a commodity that can be cut to the bone. Some argue that bringing manufacturing back to the U.S. would raise drug prices by 15-25%. But the real cost isn’t on the pharmacy shelf. It’s in the hospital. In the delayed surgery. In the patient who didn’t get their insulin. In the family who lost a loved one because a bag of saline wasn’t available.What You Can Do

You can’t build a new factory. But you can stay informed. If you or a loved one rely on a critical drug-insulin, chemotherapy, IV fluids, epinephrine-ask your pharmacy or doctor: Do you have a backup plan if this drug disappears? Ask your local hospital if they’re part of any regional drug-sharing networks. Support policies that fund supply chain resilience. Pressure lawmakers to fund the FDA’s new initiatives. This isn’t just a health issue. It’s a safety issue. The next hurricane is coming. The next flood is coming. The question isn’t if another drug shortage will happen. It’s whether we’ll be ready when it does.Why do drug shortages happen after hurricanes?

Hurricanes damage power grids, flood manufacturing plants, and destroy transportation routes. Many U.S. drug factories are concentrated in hurricane-prone areas like Puerto Rico and North Carolina. When these facilities shut down, there’s often no backup-especially for sterile injectables like saline and insulin, which only have one or two producers nationwide.

Which drugs are most at risk during natural disasters?

Sterile injectables are the most vulnerable-things like IV fluids, antibiotics, insulin, chemotherapy drugs, and epinephrine. These drugs require complex, sterile manufacturing environments and have very few production sites. Generic drugs are especially at risk because they’re low-profit, so companies don’t invest in multiple factories or backup systems.

How long do drug shortages last after a disaster?

It depends on the damage. Hurricanes typically cause 6-18 month shortages because they destroy infrastructure like power and water systems. Tornadoes or localized events may cause 3-9 month shortages focused on specific drugs. Rebuilding a drug manufacturing line takes 6-12 months, and getting new equipment can take 2-3 years.

Is the U.S. government doing enough to prevent these shortages?

Not yet. While the FDA has started new programs like the Critical Drug Resilience Program and proposed emergency inventory rules, most pharmaceutical companies still haven’t implemented meaningful changes. Only 31% have taken real steps to reduce risk. The system is still built for low cost, not disaster readiness.

Can I stockpile my own medications in case of a shortage?

For some medications, yes-but only under your doctor’s guidance. Never stockpile insulin, chemotherapy, or injectables without medical advice. Some drugs degrade if stored improperly. Talk to your pharmacist about getting a small extra supply if you’re on a critical medication and live in a disaster-prone area.

Are other countries facing the same problem?

Yes, but differently. Countries like Iran have more distributed manufacturing, so a single disaster doesn’t wipe out the entire supply. The U.S. problem is extreme concentration. Other nations also face shortages, but the U.S. is uniquely vulnerable because of its reliance on a few key locations and its just-in-time inventory model.

December 11, 2025 AT 06:45

Aileen Ferris

so like... iv fluids are just... gone? like, how is this even legal? we cant even have a bag of salt water when we need it? lol. the system is broken. and no one cares until someone dies.

December 12, 2025 AT 01:57

Sarah Clifford

THIS IS A DISASTER AND NO ONE IS TALKING ABOUT IT. I HAVE A KID WITH DIABETES. WHAT IF THE NEXT HURRICANE TAKES OUT THE INSULIN FACTORY? THEY’RE NOT EVEN TRYING TO FIX THIS. IT’S NOT A CONSPIRACY, IT’S NEGLIGENCE.

December 13, 2025 AT 19:38

Ben Greening

The structural vulnerability of pharmaceutical supply chains has been well-documented for over a decade. What’s new is the acceleration of climate-related disruptions. The concentration of sterile manufacturing in coastal regions was a cost optimization that ignored systemic risk. This is not an accident-it’s a predictable failure.

December 15, 2025 AT 17:30

Mia Kingsley

okay but like... why do we even make drugs in puerto rico? like, it’s a hurricane magnet. and no one thought to put a backup somewhere else? i mean, we have space stations and self-driving cars but we can’t make saline in 3 states? what even is this?

December 16, 2025 AT 08:04

Aman deep

i’ve worked in rural clinics. when the meds run out, we don’t have a backup. we don’t have a team to map supply chains. we just pray. i’ve seen nurses stretch one iv bag to last two patients. no one talks about that. the system doesn’t see us. and now climate change is just making it worse. we need help, not just more reports.

December 18, 2025 AT 04:39

Sylvia Frenzel

this is why we need to stop letting foreign countries make our medicine. america used to make its own drugs. now we’re dependent on a few buildings in hurricane zones. it’s embarrassing. we need to bring this back home. no more outsourcing our health.

December 18, 2025 AT 19:19

Regan Mears

I’ve been saying this for years: redundancy isn’t expensive-it’s cheaper than death. When a single line shuts down and 27 drugs vanish? That’s not a glitch. That’s a design flaw. The FDA’s new rule is a start, but it needs teeth. Mandate multi-site production. Tax companies that refuse to diversify. We’re not asking for miracles. We’re asking for basic safety.

December 19, 2025 AT 10:03

Vivian Amadi

you people are panicking over saline? get real. people die every day from bad healthcare. this is just another headline. if you can’t afford your meds, that’s your fault for not having insurance. stop crying and get a job.

December 21, 2025 AT 01:19

matthew dendle

so the pharma companies are lazy and the gov is slow and the climate is mad... guess what? nothing changes. we all die. eventually. at least the iv bags were cheap while they lasted lol

December 22, 2025 AT 19:11

Jean Claude de La Ronde

We treat medicine like water from a tap-turn it on, it flows. But it’s not. It’s a fragile, human-made miracle built on globalized fragility. When the storm hits, we don’t lose power-we lose the ability to sustain life. And we act surprised? We built this. We chose efficiency over survival. Now we reap the silence.

December 24, 2025 AT 15:23

Jim Irish

The disparity between urban hospitals and rural clinics is staggering. The 3.2x difference in supply chain mapping isn’t just data-it’s a death sentence for people in Appalachia, the Delta, and the Navajo Nation. Resilience must be equitable. Not optional.

December 25, 2025 AT 02:10

Jimmy Kärnfeldt

i know it feels hopeless but we’ve fixed worse. remember when the opioid crisis hit? people got loud, lawmakers moved, companies changed. this is the same. we just need to care as much. talk to your rep. donate to community clinics. share this. small things add up.

December 26, 2025 AT 05:38

Ariel Nichole

this is actually really well written. i didn’t know any of this. i always thought drugs just... appeared in the pharmacy. i’m going to ask my doctor about backup plans now. thanks for sharing this.

December 26, 2025 AT 21:21

Stephanie Maillet

I wonder... if we treated medicine like we treat electricity-distributed grids, backup generators, regional redundancy-would we be here? We don’t let one power plant take down a whole city. Why do we let one factory take down a nation’s insulin supply?

December 26, 2025 AT 23:11

David Palmer

i dont care about your iv bags. the real problem is that the rich get their meds and the poor die. this is just capitalism being capitalism. you want change? burn it all down.